THE DESIGN OF EVERYDAY VR THINGS

Written by Pierce McBride

If you read my last post on this blog, Developing Physics-Based VR Hands in Unity, you’d know that I think hands are the most interesting aspect of virtual reality (VR) game design. All the things we as humans do with our hands have existed in games, sure. Games have doors you can open, buttons you can press, and objects you can throw, for example. But these interactions have to be mediated by the mechanical objects we call controllers, keyboards, and mice. These objects force us to simplify what you, the player playing the game, must physically do to make your avatar do something in return. Opening a door or pressing a button becomes pressing X. Throwing a ball becomes flicking an analog stick.

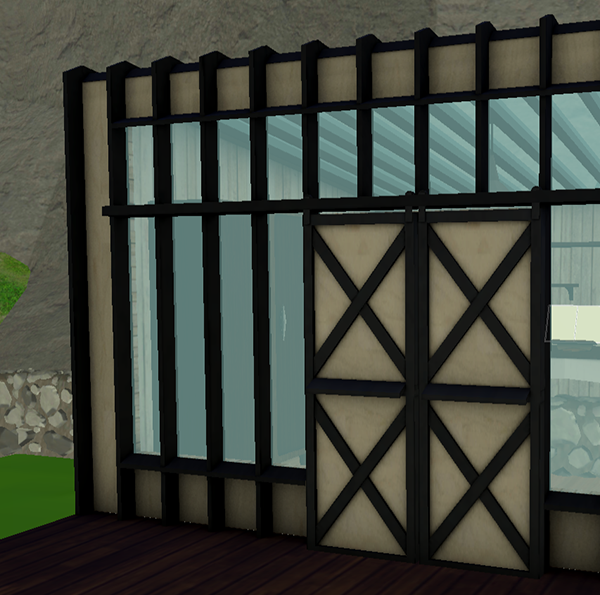

Even if our doors are virtual, we still use them like real doors.

These work fine, but VR offers something more tactile, but therein lies the challenge, both for us at Amebous Labs as well as any developer working in VR. In VR, we have a 1-to-1 mapping of your physical hand’s position and rotation. We also have a pretty good approximation of your hand “gripping” in the grip or trigger buttons, depending on your platform. That’s pretty cool! It means we can make a virtual door that you physically grab and physically pull open, just like a real door. Now you might not need that “Press X to” prompt on the screen. Who needs help opening a door? As it turns out, a lot of people. Exchanging a controller for a hand just changed the kind of design we need to think about.

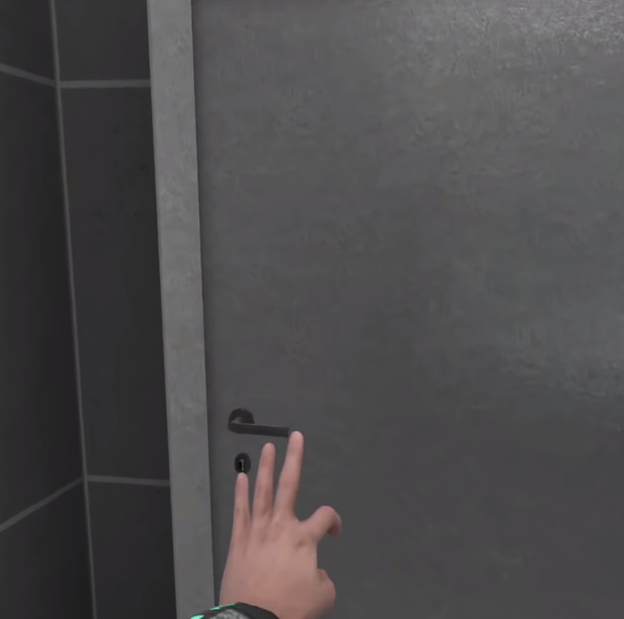

Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare

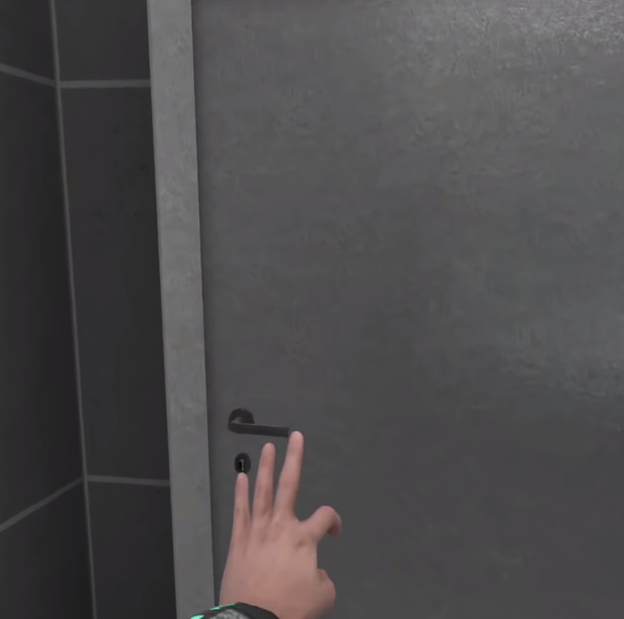

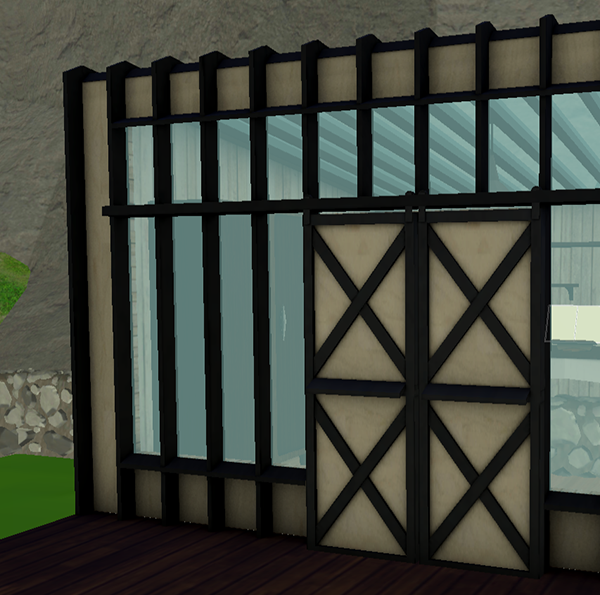

In fact, confusing doors is literally an issue so common in the broader field of design that it’s a joke unto itself. They’re called Norman Doors, named after Don Norman. Norman wrote a very influential book on a design called The Design of Everyday Things. The book is about usability and ergonomics, which are fields of study about how the shape, placement, color, and other factors of objects in our world teach us how to use them or how they work. One of the more famous examples of the confusing design is door handles. To Norman, the shape indicates not just how you grasp the door but also what direction it swings or slides. These factors are just as important in VR precisely because hands are how we use them. Even if our doors are virtual, we still use them like real doors. For example, in Boneworks, your VR body can collide with doors, but they often have you pull open doors. They get the handles right, and the shape suggests grasping and pulling. However, the doors sometimes swing inwards. That’s tough in VR because it’s hard to move your body around the door as you open it. The game is otherwise great! But I often accidentally bumped doors closed when opening them or trying to walk around them. In Loam, we’re planning on using sliding doors to alleviate this problem.

Door in Boneworks

Door in Loam

This kind of thinking really should impact any portion of VR design that involves the player. In Vacation Simulator, you can adjust the height of most tables, so they’re comfortable for how you’re playing. In Loam, we put the handle of the watering can on the back so you wouldn’t have to tilt your wrist as much as you play. We even picked a long, normally two-handed shovel and not a trowel because we don’t want to make players bend down repeatedly. This only scratches the surface of the field, and I’d recommend all designers, but especially VR designers, to look for solutions in the way actual objects solve similar problems.

Oh yeah, and read The Design of Everyday Things.